We are told by educators and business leaders today that we need to be nimble for the job market. We are told that in a world with no borders, having an entrepreneurial mindset is the key – a remedy for all the contract work and ‘tasks’ that now masquerade as jobs.

We haven’t been told lies – this is all well and true. But we aren’t being told the whole truth, either.

The truth is that having such an attitude and stance is not enough. For most, there will be many times when one contract ends and another won’t begin seamlessly.

A study by the United Way and McMaster University from 2013 shows that only half of the people in the Greater Toronto Area, for example, have standard, full-time jobs. Obviously this means that precarious work is not just for minimum-wage, service-oriented jobs. Precarious work is the new norm for highly-trained technological workers, nursing staff, professors, engineers, and in fact, most professions.

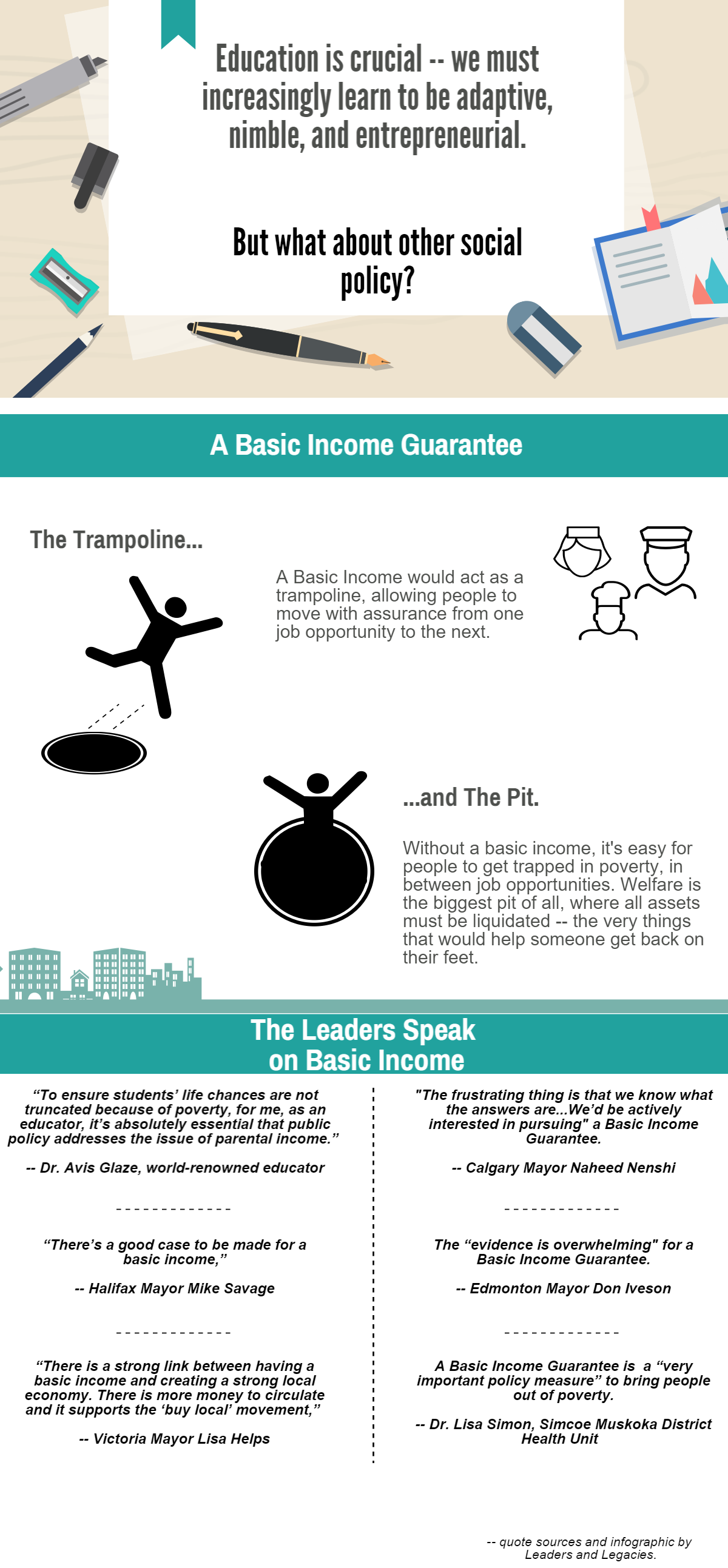

How a Basic Income Would Help

A basic income – ensuring no Canadian would ever drop below the poverty line – would be the best way to protect people from these new realities. Let’s say it was set at $20,000 per year. If someone earned $14,000 in one year, then at tax time an additional $6,000 would be given to that person, spread out over 12 months using the existing income tax system. Clean and simple and minimal bureaucracy. No one is overseeing the process to determine if it is ‘deserved.’ We could scrap the entire welfare system and review other levels of bureaucracy, too.

A basic income would ensure that in between these projects and short-term jobs we provide a trampoline for people to bounce into their next opportunity – rather than the hole or pit that currently exists and is difficult to climb out of, each and every time.

For some, all it would take is two or three rocky months in a row while looking for work to become dangerously impoverished – and our welfare system is the biggest pit of all, where every asset must be liquidated to receive a shockingly small amount of money.

Educators are reacting to the shifting needs of business and are, themselves, trying to do their best to ensure students are ready with relevant skills and knowledge and a capacity for lifelong learning that meets the needs of the marketplace.

But this is an incomplete answer for how to build a society. It illustrates part of the reason, in fact, why education alone cannot solve all social problems. We must also examine how we take care of our people from a social policy standpoint.

Not everyone has the capacity to be entrepreneurial, and all the education in the world will not make them so. That’s why we need to set up a basic income guarantee for anyone who needs it. All of us would have access to this minimum standard of living, should we ever have the need.

Fortunately, there are numerous examples from around the world, including Canada, where some form of basic income has been tried.

- In part of Namibia where an unconditional basic income grant was tried, child malnutrition dropped from 42 per cent to 10 per cent, with close to zero dropouts from school.

- In a World Bank study, researchers gave cash transfers to families in Malawi and ended up increasing school attendance of females with the program because they could afford to go to school to better themselves and their families.

- In eight villages in India, economist Guy Standing reports there was improved housing, better nutrition, better health outcomes, improved school attendance, and more empowerment for those with disabilities.

“Contrary to the skeptics,” writes Standing, “the grants led to more labour and work…There was a shift from casual wage labour to more…self-employed farming and business activity, with less distress…”

There will always be people who abuse the system (there are now, in fact) and this will always, thankfully, be a very small percentage. As studies from around the world show, most people are hardwired to do something — to want to make a meaningful contribution of some kind.

As educators work hard to prepare young people to be adaptive and entrepreneurial, our federal and provincial governments should be working hard to adopt this forward-thinking social policy.

We shouldn’t have one without the other.

— Roderick Benns is the publisher of Leaders and Legacies.

Leaders and Legacies Canadian leaders and leadership stories

Leaders and Legacies Canadian leaders and leadership stories